Building the Strategic Team for Collaborative Problem Solving

LEARN MORE:

Resources

Building the Strategic Team for Collaborative Problem Solving

This note sets out some ideas about how civic leaders (e.g., mayors or public managers) can form a strategic team, drawn from different government agencies, nonprofits, foundations, and corporations, that can work across organizational boundaries to design and implement a collaborative solution to a complex problem.

By George Veth and Mark Moore

Introduction

Faced with a Challenge

Imagine you are the mayor of a medium-sized U.S. city, and, for the third day straight, a large protest has been held opposite police headquarters. Last week, police who were responding to a mental health crisis shot and killed a young man holding a knife. When body cam footage was released to the public, many said the man posed no immediate danger to those on the scene: yes, he was holding a knife and appeared agitated, but he was ten feet away and not advancing toward the officers. In the wake of this tragedy, there has been a massive public outcry, as residents point to the history of officers in the city shooting those in the throes of mental health crises.

A man has died, in an awful, avoidable way, and now you must do something. This is your first term as mayor, and you campaigned on, among other things, reforming the police department. You knew it would not be easy, but you now see the problem is even more complex than you had realized. Your city’s budget is tight, and it’s unclear who, besides the police, can adequately respond to the many emergency calls related to mental health crises, domestic violence, or other forms of disorderly conduct. Vocal segments of the population are calling for reforming or even defunding the police, but other constituents are asking for increased patrols of high-crime neighborhoods. Never mind the fact that the police union is a powerful force in city politics.

The issue is complicated and politically fraught, with stakeholders inside and outside the city government loudly demanding contradictory actions. Any solution will need to be complex, will require cooperation among many departments (and perhaps extra-governmental organizations, too), and will take time, significant resources, and all the political capital you can muster as a first-term mayor. The status quo is no longer tolerable, but with a problem like this, where should you even start?

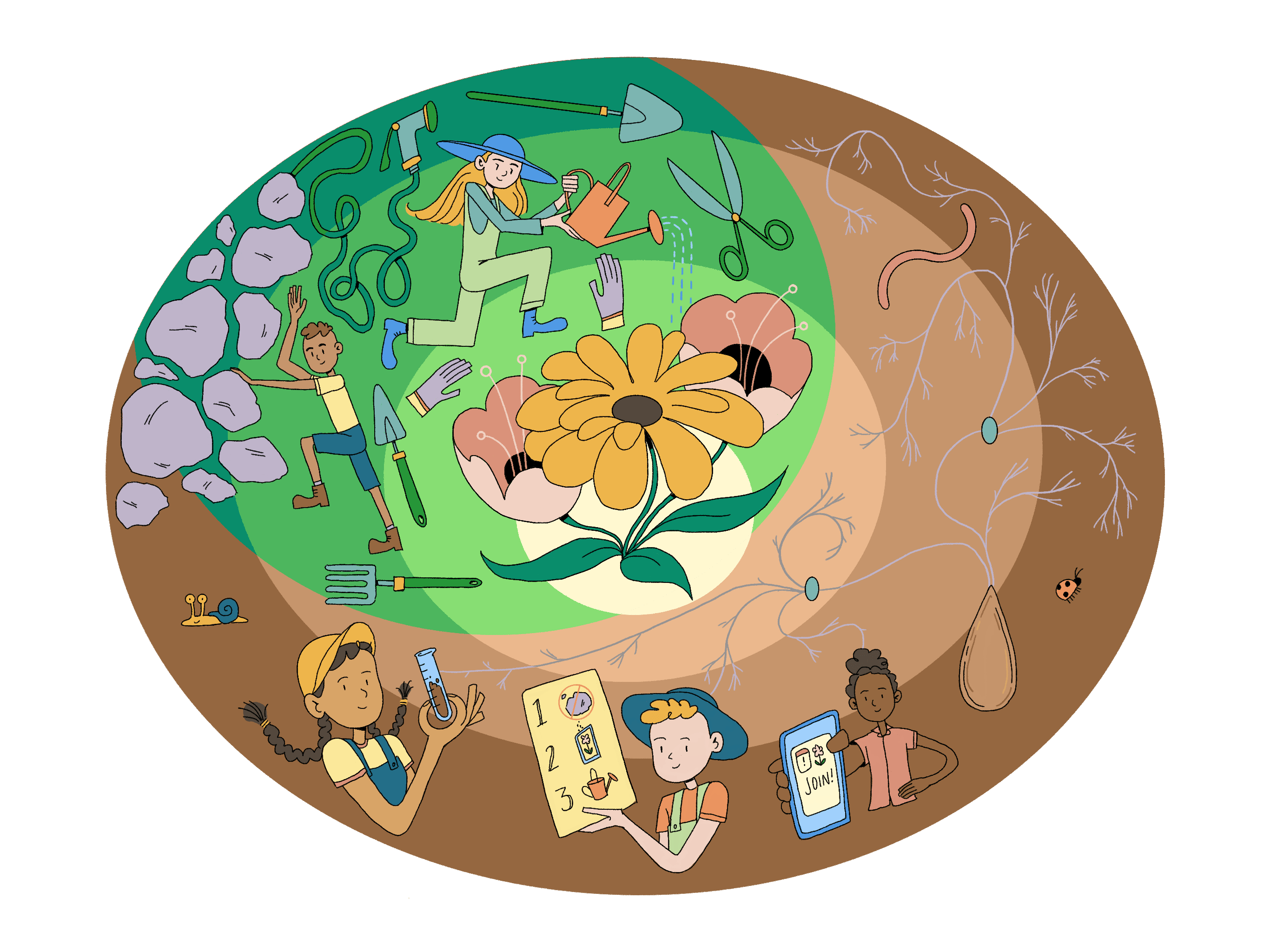

Collaborating Across Boundaries

This note sets out some ideas about how civic leaders (e.g., mayors or public managers) can form a strategic team, drawn from different government agencies, nonprofits, foundations, and corporations, that can work across organizational boundaries to design and implement a collaborative solution to a complex problem. Doing so means engaging in a dynamic process that may be broadly divided into two parts: thinking and acting. It also means forming an extended team or coalition around the strategic team, which can help enact its plan. A number of challenges arise from the complexity of this process (and of cross-boundary collaboration in general). To succeed, the initiative requires building a kind of executive capacity—the knowledge and ability to manage a complicated problem-solving process—in many ways more like running a goal-oriented grassroots campaign than like managing a staff in a hierarchical organization. The initiative also requires expertise, resources, permissions, and operational capacities (domain assets) within the specific issue environment.

This note sets out some ideas about how civic leaders (e.g., mayors or public managers) can form a strategic team, drawn from different government agencies, nonprofits, foundations, and corporations, that can work across organizational boundaries to design and implement a collaborative solution to a complex problem. Doing so means engaging in a dynamic process that may be broadly divided into two parts: thinking and acting. It also means forming an extended team or coalition around the strategic team, which can help enact its plan. A number of challenges arise from the complexity of this process (and of cross-boundary collaboration in general). To succeed, the initiative requires building a kind of executive capacity—the knowledge and ability to manage a complicated problem-solving process—in many ways more like running a goal-oriented grassroots campaign than like managing a staff in a hierarchical organization. The initiative also requires expertise, resources, permissions, and operational capacities (domain assets) within the specific issue environment.

Moreover, the individuals on the team must complement one another’s strengths and interact effectively. Once the strategic team has been recruited, decisions must be made about how best to orchestrate it (using dominating or consensus-based management styles to guide the process or, more likely, a hybrid of the two). Finally, as the dynamic problem-solving process unfolds, the composition of the strategic team may need to change to better fit individual capacities to the task at hand. Making changes in a complicated environment to create lasting positive impact is not easy, but careful consideration of the role, requirements, and orchestration of the strategic team makes success more likely.

Collaborating Across Boundaries

Before considering how to select the right strategic team to address an issue, it will help to briefly sketch the problem-solving process that such a team will drive forward.

Naming and Framing the Problem

The process really begins before the team comes into being: when a civic leader uses their formal authority, their political influence, and their hard-won knowledge of social conditions and aspirations in their communities to name and frame a particular social condition that requires improvement. As soon as the civic leader expresses an interest (or before, if constituents bring the idea to the leader), some public interest in the particular problem will be aroused. Choosing a particular problem, announcing it publicly, and inviting a discussion about that problem can help the civic leader and their team to see who is interested and concerned enough about the problem to show up at a meeting to discuss how it might be solved.

The next step, of course, would be to find a person or to form a team that will oversee and coordinate the initiative to improve the targeted social conditions—to solve the problem. However, the selection of a team will be bracketed for now and later treated in a detailed section of its own.

Thinking and Acting

Once the problem and the initial strategic actor/team have both been named, the core of the work begins. The first part of this work, exploration or “thinking”, involves analysis and planning. It is a necessary precursor to the second part, implementation or “acting”, which involves mobilizing support and resources, executing the steps chosen to resolve or ameliorate the problem, and tracking and evaluating the progress of the initiative. Of course, the process in reality is often a dynamic dance between thinking and acting, exploration and implementation.

Thinking: It is quite likely that the civic leader at the outset will lack a clear idea of the problem’s exact nature, or of the political and operational work required for the solution. In this case, the first critical work to be done is gathering data, searching for or imagining solutions, and inventorying current deployment of resources with regard to the issue. (Even if the civic leader thinks that they already have a good idea, it might still be appropriate for the team to spend some time thinking about the problem long enough to become committed to the executive’s idea.) Then, based on analysis of the situation and consideration of ways forward, a concrete plan must be selected and fleshed out.

Acting: With a plan in place, the strategic team can proceed to execute their vision. This involves expanding and sustaining public awareness of the issue, as well as emphasizing the urgency of resolving it; mobilizing the resources needed for the plan; actually changing current operations in relevant departments, agencies, etc.; monitoring progress and communicating about on-the-ground realities to enable adjustments; and evaluating the effort’s success in meeting its concrete objectives.

Acting: With a plan in place, the strategic team can proceed to execute their vision. This involves expanding and sustaining public awareness of the issue, as well as emphasizing the urgency of resolving it; mobilizing the resources needed for the plan; actually changing current operations in relevant departments, agencies, etc.; monitoring progress and communicating about on-the-ground realities to enable adjustments; and evaluating the effort’s success in meeting its concrete objectives.

A Dynamic and Iterative Process

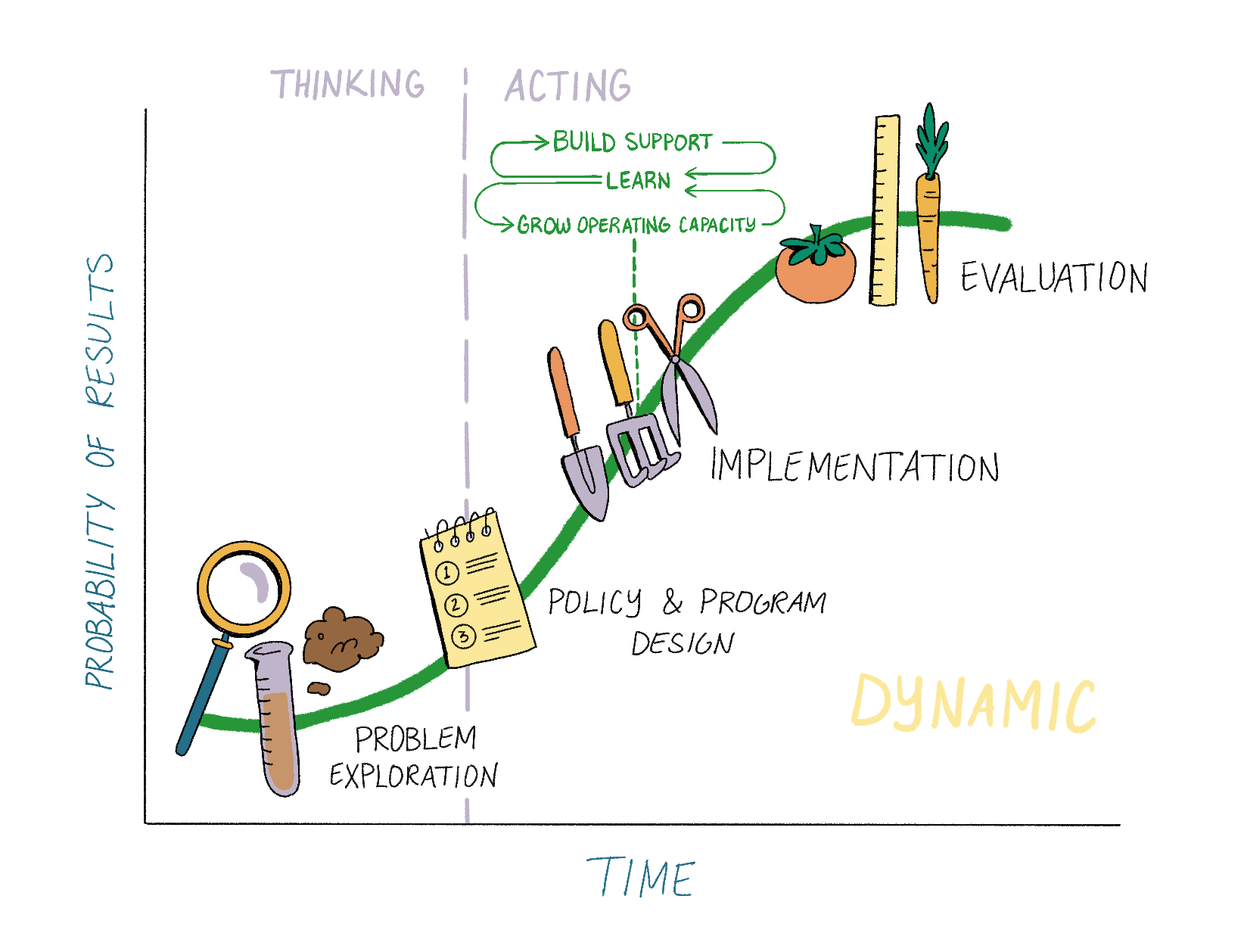

Note that this problem-solving process is dynamic. It has stages of development that can be defined in terms of the functions being performed (even if one stage does not always precede the next in a strictly linear fashion).

To illustrate the dynamism of the problem-solving process, the following figure (Functions of a problem-solving initiative) offers a schematic view of how different activities or functions might vary in importance as the initiative progresses. The functions are always being performed to differing degrees, with more or less attention and material resources being applied to them. But in the normal course of developing and implementing a collaborative solution, the salience and urgency of the functions will vary.

Functions of a problem-solving initiative

This is a simplified, linear view of the different stages of a problem-solving initiative.

This figure not only shows that the relative importance of the functions might vary over time, but also that the overall performance of the initiative varies depending on what functions are being performed. At the outset, when the collaboration is simply the glimmer of an idea, little capacity has been constructed for execution of plans, and no real results have been produced. (All that has changed is the probability that something valuable could happen, since some work has now been done to design the needed change.) Later, real material resources begin moving around and new operations begin to produce early results, not only increasing capacity (and the probability of effective action) but having real impacts.

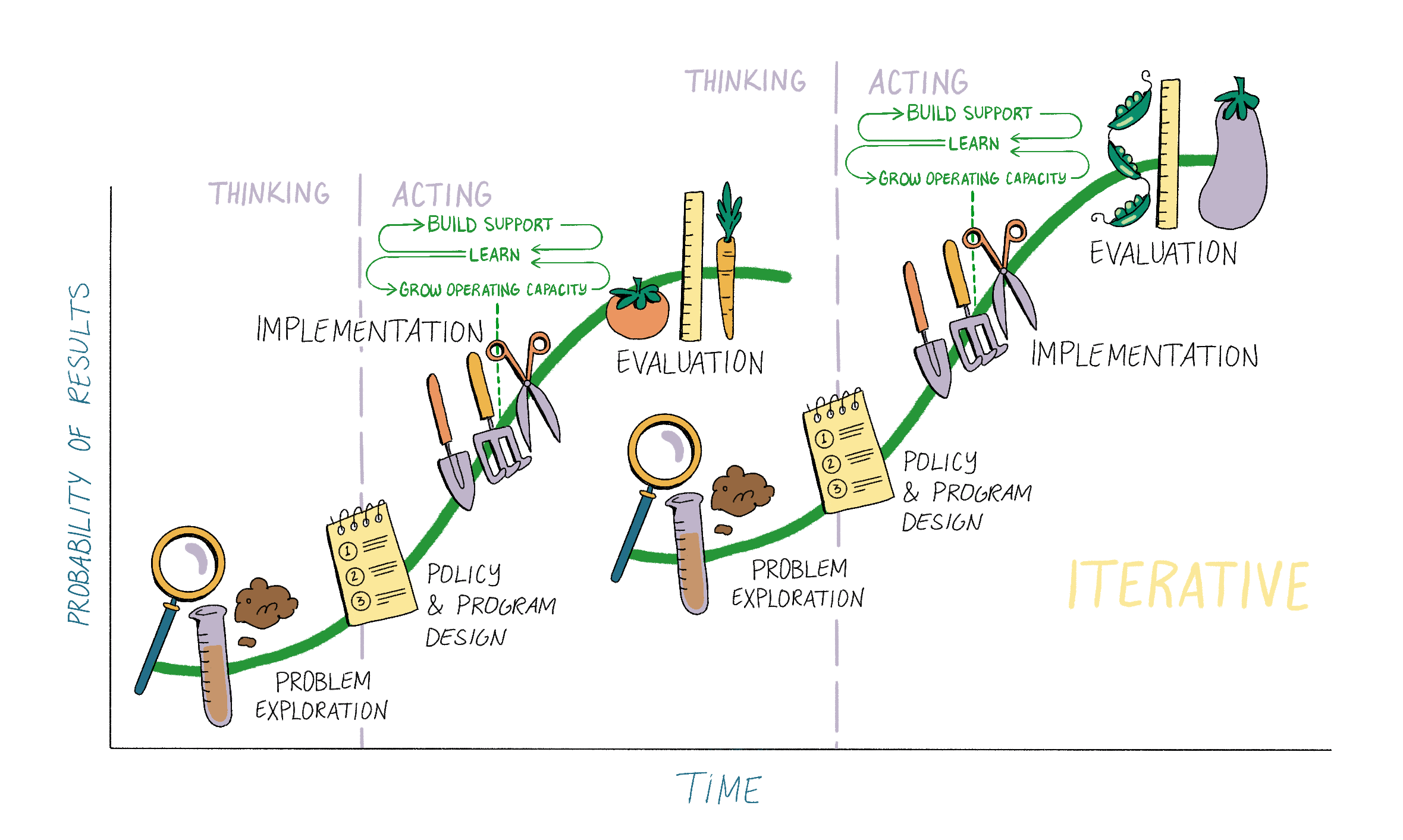

Unfortunately, most initiatives do not proceed according to plan. Indeed, very few plans survive their first contact with reality. The difficulties often show up first as failures in one or more of the sub-projects that make up the whole. But they may also manifest as unexpected and significant conflicts among participants, or unintended negative consequences of the effort. This means that the process of designing and implementing the collaborative problem-solving effort is iterative and recursive as well as dynamic: sometimes the effort might have to step backward to continue forward, as the strategic team goes “back to the drawing board” to develop a different design.

The next figure (Overlapping processes of a problem-solving initiative) shows a process in which the strategic team shifted from the original approach to one that might perform better. The process first went from an idea to mobilization of resources and transformation of operational activities, increasing the probability of achieving the desired results. Then things began to go awry (or new opportunities were spotted that seemed to have more potential). Shifting to that new approach cost something in the short run, as the shift was made, but it seemed necessary for optimal achievement of the initiative’s goals.

Overlapping processes of a problem-solving initiative

The iterative nature of solving a complex problem means functions from different “stages” of the process may in fact be performed at the same time.

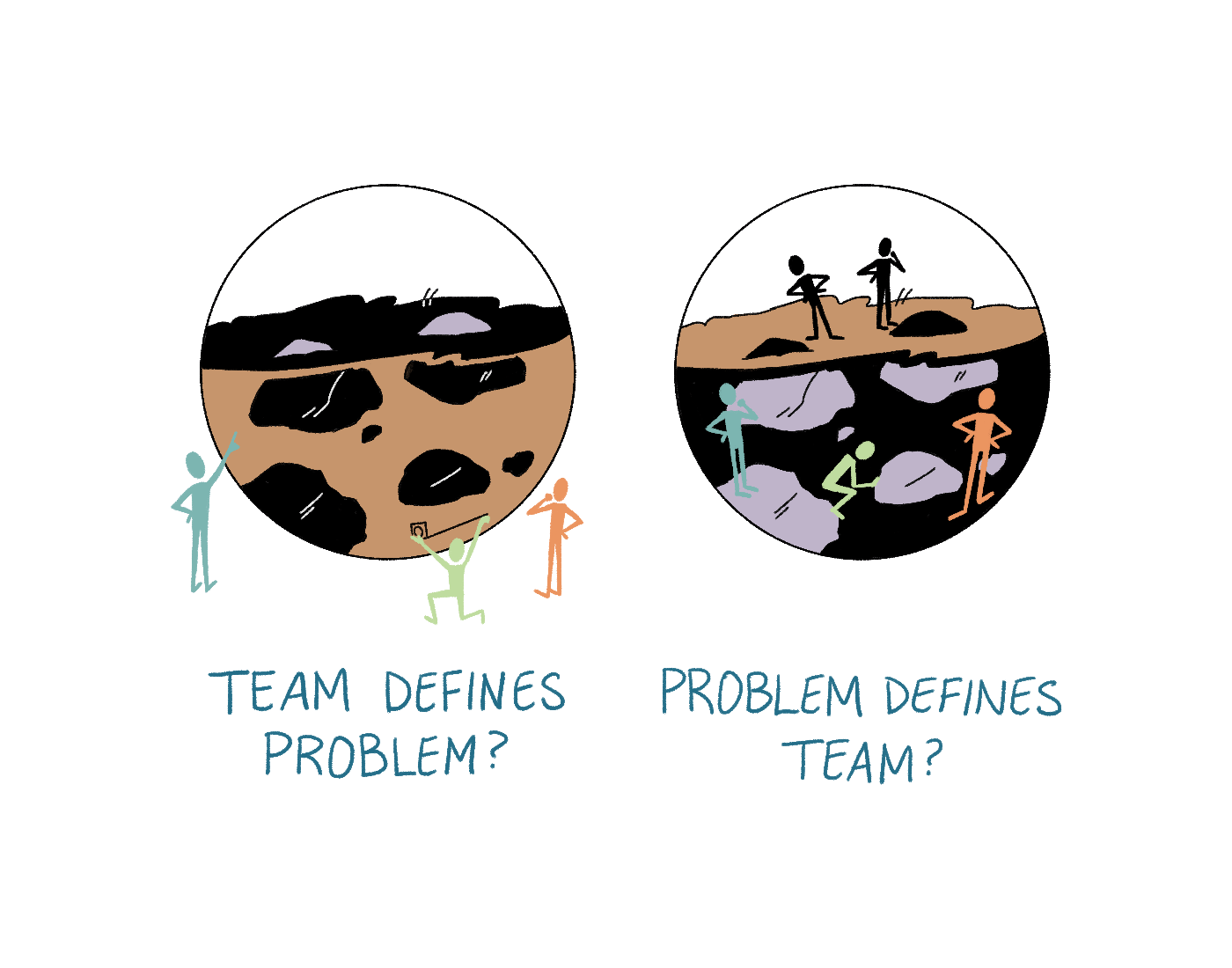

The Chicken-and-Egg Dilemma

Since the problem-solving process is dynamic and unpredictably recursive, it presents a conundrum from the very outset: should the team define the problem, or the problem define the team? In other words, a team might be selected to perform a particular set of tasks well, but then find out that the problem was different than initially thought, requiring a team with different assets and capacities! Obviously, it is difficult to rightly value the particular assets held by candidate team members until there is a substantive definition of the problem and an actionable idea about how to solve it. Only against the backdrop of that more or less detailed and concrete picture of the work to be done can the civic leader judge the capacities of particular candidates for the team and select the appropriate combination with confidence—the task explained in the next section. (Later, the topic of whether and how to change the composition of the team in response to the dynamic problem-solving process will also be discussed.)

Since the problem-solving process is dynamic and unpredictably recursive, it presents a conundrum from the very outset: should the team define the problem, or the problem define the team? In other words, a team might be selected to perform a particular set of tasks well, but then find out that the problem was different than initially thought, requiring a team with different assets and capacities! Obviously, it is difficult to rightly value the particular assets held by candidate team members until there is a substantive definition of the problem and an actionable idea about how to solve it. Only against the backdrop of that more or less detailed and concrete picture of the work to be done can the civic leader judge the capacities of particular candidates for the team and select the appropriate combination with confidence—the task explained in the next section. (Later, the topic of whether and how to change the composition of the team in response to the dynamic problem-solving process will also be discussed.)

Requirements for the Strategic Team

Clearly, putting together a strategic team appropriate to the chosen problem is not a simple matter. The strategic team needs to be small enough to effectively coordinate and decide on the appropriate course of action, yet collectively it needs to hold key assets and be capable of performing diverse functions, all necessary to the ultimate achievement of the initiative’s goals. Though the functions and assets demanded at different stages of the process are not mutually exclusive, they are quite different, making it harder to ensure all capabilities are present in one team.

Solving Problems in Hierarchical Organizations

To understand what is required of a team working across different independent organizations to improve social conditions, it will be instructive to first consider the more familiar case of solving problems within a hierarchal context.

In a public agency or a department of city government, those at the top are aided by pre-existing structures and processes that, if used correctly, can provide energy, direction, and focus to move the change initiative from an idea to a carefully crafted and tested plan, into and through the conflicts, disappointments, and surprises of implementation, and into the next cycle of evaluation and improvement. Those pre-existing structures and processes help in many ways to make the change initiative likelier to succeed.

For one thing, members of the strategic team (within a preexisting hierarchal organization) who are managing an initiative may have prior experience working with one another to execute projects, and they likely have been granted extensive formal authority over the assets – material, human, administrative, and technological – needed to make the change. This authority, combined with an organizational mandate to achieve a well-defined and broadly supported purpose, allows the strategic team to set and sustain the pace of the initiative. The strategic team also has the ability to inventory existing operational methods meant to improve the targeted social conditions, as well as the latitude to explore new operational approaches to the problem through reallocation of existing resources.

Furthermore, organizational support for the strategic team can help its members work through any conflicts that arise as resources are shifted and operational methods altered; and can insulate them from the risk that their innovative ideas might fail. In terms of accountability, the team is expected to stay in close, regular communication with the top levels of the organization, and its performance is monitored through a specialized information system (i.e., a dashboard) that tracks implementation progress by performance on concrete intermediate targets, providing early signals of whether the effort is reaching its goals.

Even in the context of a hierarchical organization’s formal centralized authority, broadly shared culture, and dense network of existing relationships, which provide so many structural advantages to the initiative, the effort to change the status quo is by no means easy or guaranteed to succeed.

Executive Capacity

When the context is instead a collaborative initiative to improve operations spread across many different independent organizations, it is clear why the challenges are far greater. In effect, executive capacity—the knowledge and ability to manage a complicated problem-solving process—must be built from scratch, to replace the structural executive capacity present in a single, hierarchical organization.

When the context is instead a collaborative initiative to improve operations spread across many different independent organizations, it is clear why the challenges are far greater. In effect, executive capacity—the knowledge and ability to manage a complicated problem-solving process—must be built from scratch, to replace the structural executive capacity present in a single, hierarchical organization.

Those trying to make a change cannot take for granted that the purposes of the change have already been defined and agreed upon, the planning for change completed, and the necessary resources mobilized. Challenges may arise at the earliest stages of defining the problem to be solved; figuring out who should be involved in the change effort; diagnosing existing operations in search of operational changes in the scale, scope, and quality of existing efforts; and identifying the specific analytical, political, and operational work that needs to be done en route to implementing the planned change and achieving the desired result.

In addition, members of a cross-boundary strategic team likely lack a history of collaboration and instead must awkwardly begin to feel out their working relationships. They will lack a complete picture of the problem to be solved, of the scale and scope of existing efforts to deal with the problem, and of the key changes needed to improve performance. Even if, among the group, they have enough information to produce a useful way forward, they will not yet have had time to share the data and reach a confident, mutually shared understanding of what can and should be done. They will lack any established structures or processes for meeting, sharing information, developing shared plans, or checking in with one another on the progress being made. They may also be uncertain about when they should add or subtract members, and what kinds of decision or consultation rights each member of the team has.

Given all the difficulties inherent to a collaboration between individuals unused to working with each other, one of the most important priorities in assembling the strategic team is finding or creating the executive capacity required to keep the initiative on track. “Executive capacity” in such an initiative is analogous to “executive functioning” in an individual—the higher-order abilities that help to order and regulate other activities necessary to survival and success. This includes things like keeping the issue at hand at the top of the agenda, evaluating the problem to see exactly what is at stake for individuals and the wider society if it persists, designing and testing possible ways to ameliorate or solve the problem, and so on.

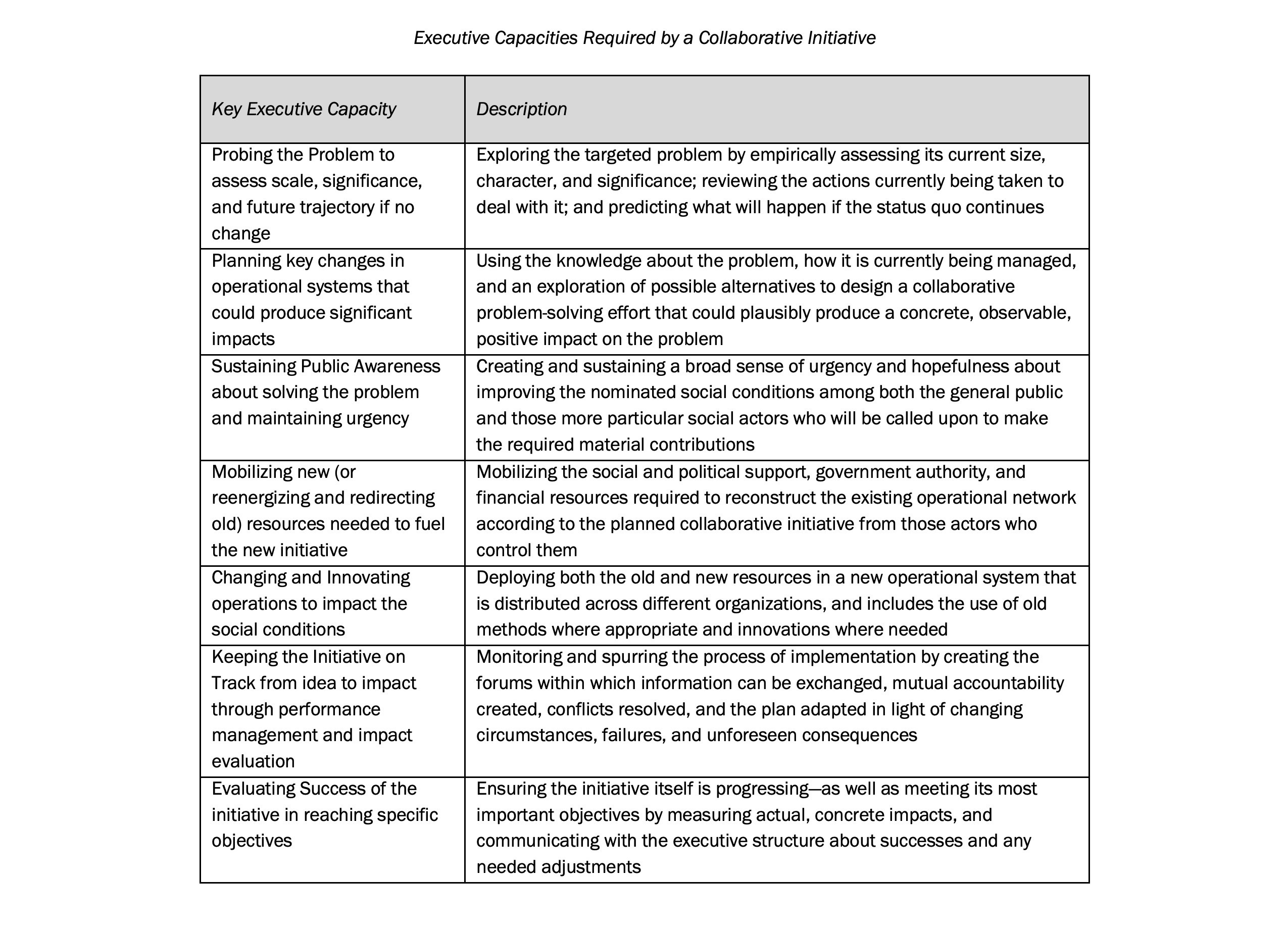

The table below presents a standard list of executive capacities needed for the change initiative to be successful.

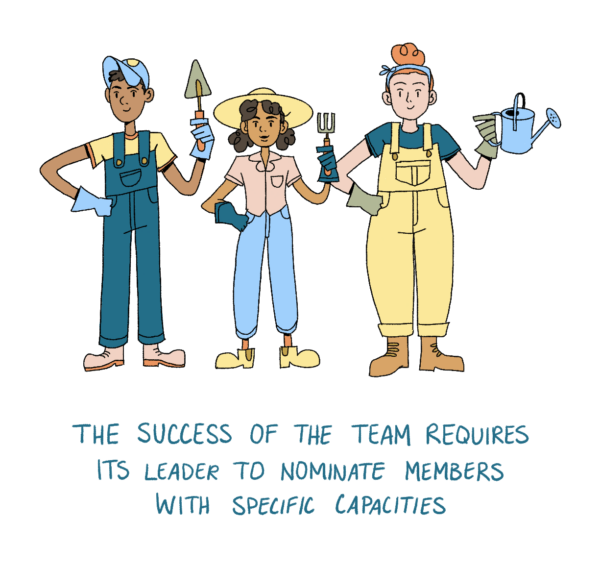

Thus, the initiative’s success requires a leader to nominate individuals with the requisite abilities to move the problem-solving process along. Remember, though, that the number of such individuals on the team may vary, and they may also possess domain assets (explained below) to greater or lesser degrees, in addition to executive capacity. The important thing is that executive capacity exists somewhere on the team and is sufficiently strong to sustain progress.

Domain Assets

As important as executive capacity is, it cannot ensure an initiative’s success by itself. The strategic team must also possess domain assets—the knowledge, experience, influence, operational capacities, and resources specific to the issue and its context that are needed to create tangible change on the ground.

Mark Moore and Sanderijn Cels suggest in their work on “Logics of Engagement” that the strategic triangle can be a useful framework while searching the local environment for individuals who might fit on the strategic team (often individuals already dealing with the problem in one capacity or another). This is because the three points of the strategic triangle correspond to different domain assets that should exist on the strategic (and the extended) teams, and thus can help narrow the search for the right kinds of actors. The domain assets are identified and described in more detail below, along with those who hold them.

Arbiters: Those with lived experience or deep understanding of the problematic issue. This is possessed by affected parties, interest groups (incl. academics), and media advocates, who all may serve as arbiters of whether the initiative is really working and is worth its costs. Arbiters are best situated to understand what is currently being done to deal with the issue, and where the problems and opportunities for improvement might lie. This domain asset corresponds to the “public value” point of the strategic triangle. Examples: Residents of a high-crime neighborhood where policing alternatives are deployed, or the students who either enroll or choose not to enroll in a new program for academic success.

Authorizers: Those with the corporate, civic, or political standing needed to mobilize the social support, political influence, governmental authorization, and financial resources required to deal with the problem appropriately. (Note that since the strategic team may eventually coordinate an extended team working on this initiative, members of the strategic team will need to bring others on board.) This asset corresponds to the “legitimacy and support” point of the strategic triangle. Examples: A board member for a foundation who can unlock funding, or a respected community leader such as an imam who can advocate and help mobilize a constituency.

Operators: Those with operational command over existing operational capabilities and resources distributed across government, the voluntary sector, and the commercial sector that could contribute to the solution of the problem, and the capacity to develop and experiment with operational methods not currently being used locally to deal with the problem. This asset corresponds to the “operational capacity” point of the strategic triangle. Examples: The head of the city transportation department, or a manager at a nonprofit that links students to volunteer tutors.

Note that domain assets are likely distributed throughout the community, as well as in different departments of an organization. Also, one person or type of person can hold more than one of these assets simultaneously—for instance, the head of a city agency who can make operational changes on their own authority but can also muster political support in other departments. Remember, too, that in different individuals these domain assets may overlap with needed executive capacities to greater or lesser degrees. (Unlike executive capacities, which are a set of generalized skills needed to keep any problem-solving collaboration on the rails and moving forward, domain assets are highly situational, depending on a particular environment, problem, and proposed solution.)

Selecting and Assembling the Strategic Team

With the above requirements for a strategic team in mind, civic leaders will be better prepared to select and recruit individuals within their local context. This is no simple task, but below are some guidelines for selecting and assembling the strategic team (some of which will also be useful when the strategic team itself begins to assemble a larger extended team to advance the initiative).

Choosing a Team, Not Just Individuals

In all likelihood, there will be many different individuals distributed across different positions with different interests and capacities who would like to become part of the strategic team, and think they deserve to be. In principle, the team should be formed by considering what executive capacities and domain assets each candidate brings to the table that could help perform the work required to solve the targeted problem. This is analogous to playing fantasy sports: one wants to draft the players who can bring the most to the goal of winning against a particular opponent. (In some cases, the civic leader may decide simply to support and continue an initiative that already exists, naming the principals in that fledgling initiative to the team, or perhaps bolstering the effort by the addition of some new perspectives or capacities.) To choose a team with complementary strengths, one has to know what assets the individuals possess, and what contributions they would make to the successful execution of the collaborative initiative.

Sometimes, civic leaders may not feel they have full discretion to appoint anyone they want. They may feel some choices have been foreclosed—that some individuals have to be included even if the executive might prefer to appoint others. However, note that this is not usually a formal restriction, but rather the result of an implicit calculation of the type recommended above. When the leader concludes that a particular individual has to be included, it is usually because she has recognized that the unwanted but necessary person holds a specific asset crucial to the success of the effort.

Sometimes, civic leaders may not feel they have full discretion to appoint anyone they want. They may feel some choices have been foreclosed—that some individuals have to be included even if the executive might prefer to appoint others. However, note that this is not usually a formal restriction, but rather the result of an implicit calculation of the type recommended above. When the leader concludes that a particular individual has to be included, it is usually because she has recognized that the unwanted but necessary person holds a specific asset crucial to the success of the effort.

In addition to selecting team members with complementary strengths, the leader should make sure the individuals, whatever other capacities they may have, can also work together as a team. Ideally, all team members should demonstrate sustained enthusiasm for participating in the collaborative effort and for solving the targeted problem, as well as strong interpersonal, organizing, and mediating skills. The leader must be concerned not only with the sum of individual capacities and assets, but also the degree to which those combined capacities and assets can be expanded or diminished by the ability of the group itself to work together.

Strategizing for Recruitment

Once potential team members have been identified, each can be assessed for their potential contribution to the initiative. This is where information gathering, analysis, and critical judgment apply. Everyone identified as potentially helpful (or else a potential hindrance, if not brought on board!) should be thoughtfully analyzed to imagine a strategic team (and eventually, beyond it, an extended team or coalition) whose combined commitments and capacities can realistically carry out the planned change.

Some of the questions to ask about potential team members are:

- What might they contribute to the effort?

- Are they critical to moving the initiative forward or to attracting others needed to move it forward? Alternatively, are they critical to not blocking or impeding the initiative?

- Are they currently inclined or disinclined toward the initiative—and how much so?

By articulating these characteristics, a civic leader can get a sense for the potential contribution of each party of interest, their criticality to the effort, and their current orientation toward supporting it.

The next step for the leader is to consider how the most critical actors might actually be recruited to the strategic team. This process could make use of existing relationships between the leader and the target individuals (or between someone who has already agreed to come on board and another candidate).

Both formal authority and informal influence can be leveraged to persuade key individuals to join the initiative. However, formal power relationships (based on positions in organizational hierarchies such as manager/subordinate) are less likely to exist in cross-boundary collaborations. Informal influence, on the other hand, is not derived from structural aspects of one’s position or role but instead from things like appealing to moral values to mobilize others, harnessing critical moments (such as crises) to influence action, or leveraging existing coalitions to recruit new contributors.

Regardless of which recruitment strategy(ies) is appropriate to a particular initiative, the civic leader must move carefully and intentionally to assemble the best possible strategic team for the task at hand. This should be the result of thorough analysis of the environment to identify and sort actors of interest who together possess the full set of executive capacities and domain assets needed to achieve the project’s impending objectives.

Orchestrating the Team

Once the strategic team has been identified and recruited, the next challenge is to orchestrate it—to run a process to maintain it, coordinate it, and to use it to make critical decisions. This task of orchestrating the strategic team often falls to a team leader, usually an individual. (It is possible for the orchestration function to be shared among the entire team, but this often leads to unwieldy project leadership and an unclear administrative decision-making process.) The role of this team leader, or orchestrator, vis-à-vis the strategic team is analogous to the role of the strategic team to the larger extended network: in both cases, the orchestrator must oversee, motivate, and coordinate a process to ensure effective, coherent action.

Orchestrating the strategic team is complicated by several factors (as noted in the discussion of problem-solving in a hierarchical versus cross-boundary context), including the team’s diversity of viewpoints and experience, the lack of preexisting relationships, and the absence of established structures and authorities to guide and drive progress. But with enough thought and care, the orchestrator(s) of the strategic team can oversee a process to manage its progress effectively.

Functions and Modes of Orchestration

According to the researchers Charlotte Reypens, Annouk Lievens, and Vera Blazevic, in their article “Hybrid Orchestration in Multi-stakeholder Innovation Networks: Practices of mobilizing multiple, diverse stakeholders across organizational boundaries,” orchestration of networks focused on innovation encompasses three functions: connecting, facilitating, and governing. That is, coordinating cross-boundary collaboration involves stewarding connections among actors; assuring harmony between them; and creating an effective network system for continued progress.

Reypens, Lievens, and Blazevic also identify three main modes of orchestration that are employed in these innovative networks: dominating mode, consensus mode, and a hybrid of the two. The first of these, the dominating mode, is closer to that employed in a hierarchical organization, where the orchestrator sets goals and gives orders more or less unilaterally. This approach has advantages as the network grows larger, since consensus is more difficult to achieve when members know each other less well and have more trouble communicating among themselves. Most likely in a collaborative network, the use of a dominating mode will mainly manifest itself in how the team leader manages the team processes.

On the other hand, the consensus mode of orchestration requires a higher degree of trust throughout the network, as individual actors negotiate with each other to arrive at a shared understanding of the work, the priorities, and which actions to take. Though consensus grows harder as the network grows in size, this mode has advantages where the network is more diverse and less likely to accept an outside authority (particularly when knowledge is diffused through the network, meaning the central authority may know much less about the issue and initiative than other individual nodes do).

The researchers emphasize that orchestrators of many innovative networks actually employ a hybrid mode of orchestration with elements of both domination and consensus: seamlessly shifting between those two poles over time, as the process unfolds, or employing domination and consensus simultaneously. Regardless, the choice of orchestration mode is a judgment call of the team leader and should be adapted as circumstances change.

Other Considerations for Orchestrators

In addition to the above observations on the functions and modes of orchestration, here are a few other general considerations regarding the orchestration of strategic teams. Though we do not develop each consideration, their import is real and something to pay heed.

- Teams, as a whole, are more than their component parts. The complementary strengths of members, and that of their aggregated potential, should be emphasized by orchestrators.

- Teams can be energized by their group identity. Orchestrators should work to give the strategic team a sense of its purpose and uniqueness, as well as a sense of the mission’s urgency.

- Both virtuous and vicious spirals are likely, especially during the early stages of a team’s work together, so orchestrators should work hard to inspire the former by recognizing and celebrating early successes, etc.

Changing the Team

Though neither selecting, nor assembling, nor orchestrating the strategic team is simple or easy, the next issue is a particularly thorny one for leaders to address: how and when to change the members of an existing strategic team.

The Need to Adapt

As noted earlier, the challenging effort to create positive change through cross-boundary collaboration is complicated by the dynamic and iterative nature of the problem-solving process. Therefore, to keep the collaboration progressing toward success, the composition of the strategic team itself may need to change over time—members may need to leave or be added. That is, at any given time, the strategic team should ideally be suited to the particular stage of development and work of the collaborative initiative.

For instance, near the beginning of the problem-solving process (in the “thinking” phase), the strategic team might require more knowledge and imagination to size up the problem and brainstorm potential interventions. Later (in the “acting” phase), the team might benefit more from the political chops required to mobilize social, political, and financial resources, and the managerial authority to deploy existing assets in new configurations or to use newly available assets to innovate and experiment with new activities and programs.

In each case, the key to assembling (and re-assembling) a strategic team with the required capacities is to maintain a high degree of congruence, between: 1) the specific assets held and deployed by the individuals on the team, and 2) the work that is immediately at hand - so as to not impede progress in solving the targeted problem.

Perhaps, if the civic leader chooses the original strategic team well enough, and if the team members succeed in transforming themselves to meet each challenge that surfaces, the same group might be able to bring the initiative to fruition by growing more committed, more knowledgeable, more focused, and more functionally capable than they were at the outset.

However, given the dynamic, recursive nature of designing and implementing a collaborative solution, it is more likely that the civic leader or the strategic team itself will have to make changes in the individuals who constitute the strategic team as the process moves forward. If the process evolves over time (which it certainly does), if it hits snags and new problems have to be overcome (which will almost certainly occur), then the initiative has to have some capacity to change the composition of the strategic team, so that it can move the project forward in its new phase or configuration.

Approaches to Restructuring the Team

In adapting the strategic team of individuals to the changing shape of the problem-solving process, several different structural options exist.

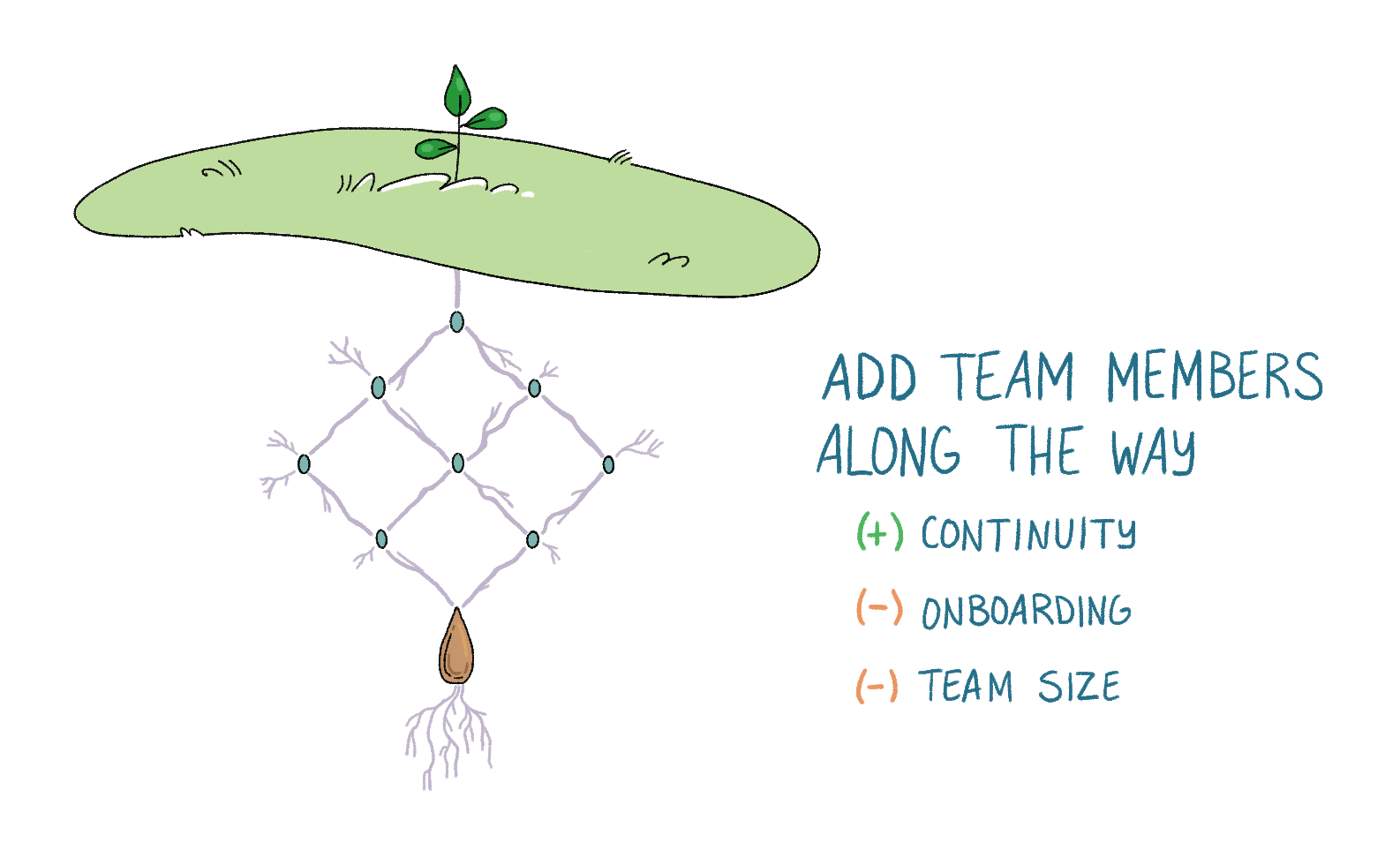

Adding Members: One possibility is that the original strategic team could simply add new members until they collectively possessed all the capacities and assets required to meet the immediate and impending challenges of the initiative. This would have the virtue of continuity but would have the disadvantages of the need to bring new individuals on board (possibly opening back up past deliberations, agreement on common language, etc..) as well as the orchestration challenges associated with enlarging the size of the strategic team.

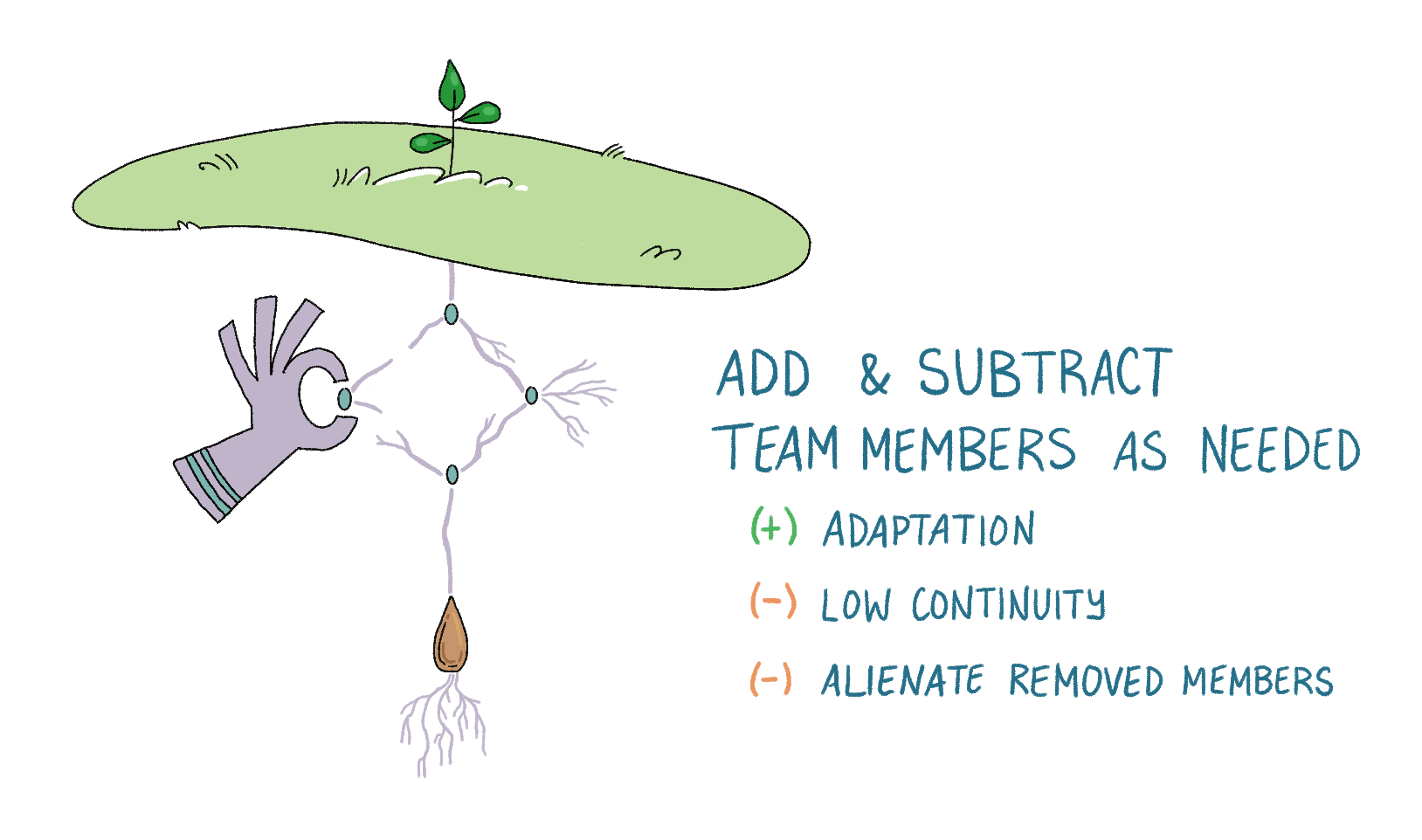

Adding and Subtracting Members: A second possibility is that, to keep the group small and manageable, some members of the original team whose assets seemed less valuable than they did at the start could agree to give up their seat in favor of others whose assets had acquired increased importance as the process went forward. This would have the virtue of adapting the group to the problems at hand, but at the price of disrupting continuity, and potentially alienating those members of the original group who were asked to stand aside.

Reconfiguring the strategic team by adding and subtracting

As the needs of the initiative change, the strategic team could add and subtract members.

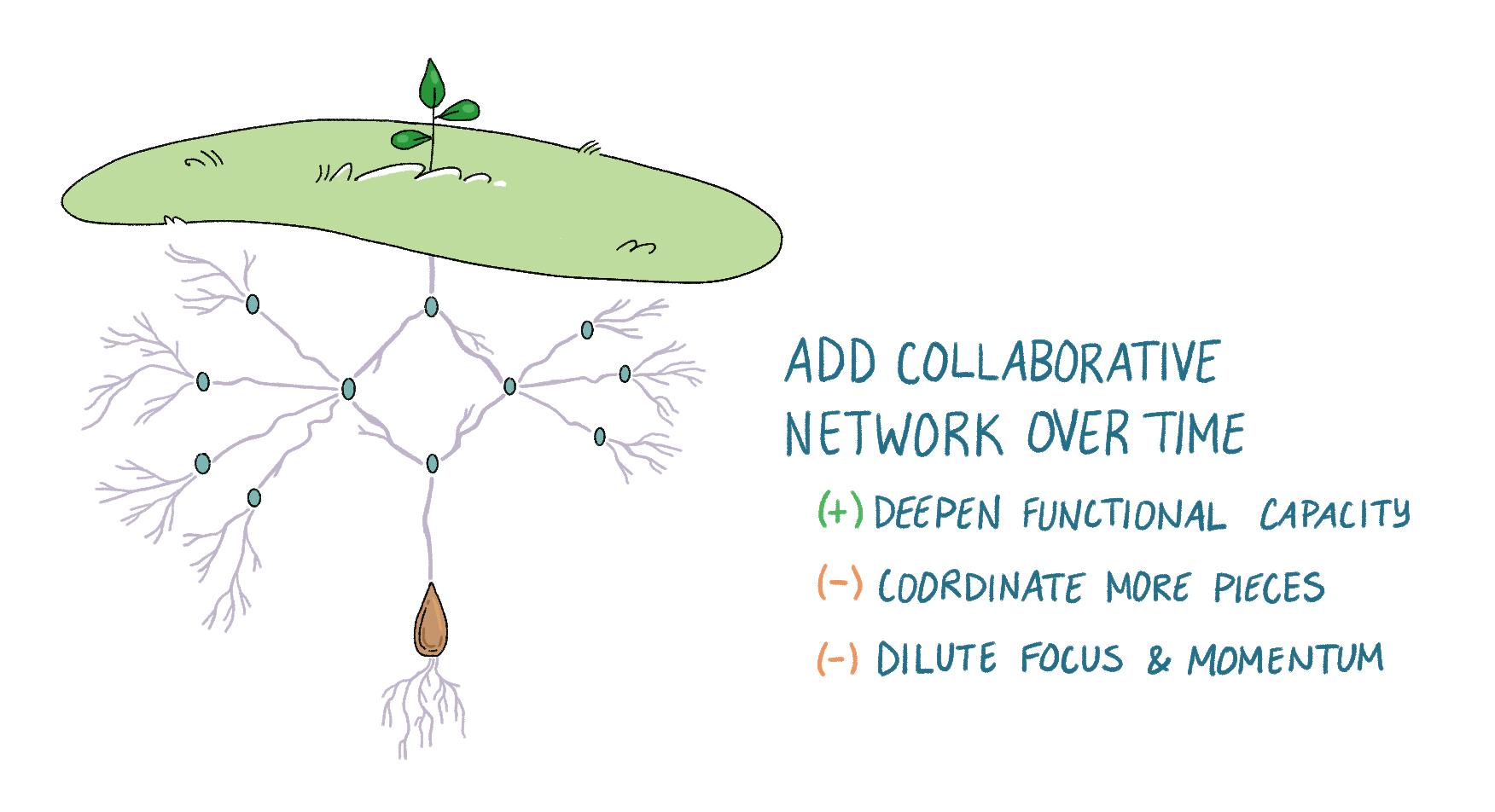

Adding a Collaborating Network: A third possibility is that the original team could continue in some specialized functional role appropriate to their individual and combined assets, while new strategic teams are assembled to deal with problems that arise in the process – such as problems of planning, constituency building, resource mobilization, or operations. This has the advantage of widening and deepening the functional capacity of the strategic team by adding individuals with assets suitable for executing a larger number and wider variety of tasks necessary to the initiative. However, it runs the risk of diluting focus and creating significant coordination problems among the increasingly widespread and dispersed sub-project teams.

This third possibility might more appropriately be described as a strategic team intertwined with a collaborating network. The idea is that, as the network of operational assignments expands to a larger, wider, more diverse group of actors spread out over the political and organizational landscape, the functions of the strategic team might come to look more like those associated with the top of a hierarchical organization (e.g., political efforts to sustain a sense of urgency about solving the problem; the development of specialized information systems to track progress against intermediate and long-range targets; the orchestration of meetings; and so on). In contrast to this “executive” strategic team, the collaborating network would be a much larger group of individuals in sub-project teams distributed across different political settings and operating organizations, holding different assets to be used for the many different tasks of the collaborative effort (e.g., design, monitoring, evaluation, resource mobilization, and operational deployment of resources).

Both the figure on “Adding or Subtracting members” and on “Sub-project teams” illustrate potential paths of development that the original group might take as they and their sponsors seek to develop the capacity needed to advance the collaborative initiative.

The strategic team with representatives from sub-project teams

As the initiative scales, the strategic team may need sub-project teams to coordinate functional work. These sub-project teams may then be represented by a person or persons on the strategic team.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the problem of adapting the strategic team to each successive stage of the problem-solving process. Instead, the decision-maker(s) must use their best judgment about what team of willing people, in their situation, is likeliest to yield long-term success.

Conclusion

Recall the situation from the introduction: a tragic death. Clamoring and contentious stakeholders. No clear path forward. No matter the impetus, collaborating across boundaries to innovatively address a complex problem is hard work. The process of making change is long: the problem must first be named and framed, after which it must be thoroughly explored, and only then can solutions be implemented—which may or may not work. To make matters worse, this process is not a linear one, but a dynamic and recursive one, often requiring those working on the problem to return to the drawing board.

Success depends on a civic leader assembling the right strategic team. This small group of dedicated and able actors will oversee each step of the problem-solving process, eventually building and coordinating an extended network around themselves. Members of the strategic team must have complementary strengths, collectively possessing the executive capacity to move the process along, the domain assets to help them understand and intervene productively in their particular context, and the motivation and interpersonal skills to work together well.

Once potential team members have been identified in the local environment, the civic leader must decide how precisely to bring them on board. After they have been recruited, decisions must be made about who should orchestrate the strategic team and how, with the mode of orchestration ideally adapting to the changing circumstances. Finally, the composition of the strategic team itself should also adapt to the fluctuating needs of the problem-solving process. Hard as all this is, with forethought, dedication, the right resources, and perhaps some luck, the initiative can yield that rarest of fruits: an innovative and successful intervention to address a challenge so complicated it had been thought insoluble.

A collaboration between George Veth and Mark Moore, the originator of Public Value Theory.