Introduction to the Public Value Canvas

LEARN MORE:

Resources

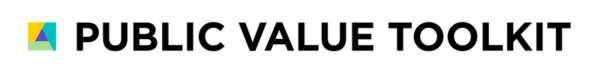

Introduction to the Public Value Canvas

A sketch board for envisioning and evaluating social change initiatives

By George Veth

Introduction

Every community has challenges, whether they are obvious or less visible: homelessness, underperforming educational systems, lack of affordable housing, addiction, insufficient green space, health disparities, and many, many more. Civic leaders, public servants, and social entrepreneurs chose their careers to improve such social conditions. However, experience quickly shows how difficult it is to get from a problem to a solution. Furthermore, conflicts over how best to address an issue raise a related question: is a given solution really worth its costs?

Public Value Thinking is a framework created by Mark Moore that can help with both concerns: how to successfully advance from problem to solution while also ensuring that the benefits of making a change outweigh the price. In short, public value is a concept of the common good that emphasizes concrete, observable benefits to society as a whole. These benefits, which may be based in different concepts of what is good and just (such as equity, dignity, freedom, and material well-being), must always be balanced against their costs (including not only money but also inconveniences, the imposition of governmental authority on citizens’ lives, and so on).

Below is a short explanation of an important aid to making such change. It is a practitioner’s tool called the Public Value Canvas, which provides a framework for conceptualizing and evaluating important elements in public value thinking.

The Public Value Canvas

The Public Value Canvas is a tool that change agents can use to help them navigate the difficult process of improving social conditions while ensuring the new status quo, or envisioned future, is worth the costs. This canvas is a visualization that can be thought of as “the big picture”: it brings together several important aspects of the problem and the change process so that users can develop and evaluate their idea for change, making sure all parts are aligned. Critically, this big picture will change over time: improving social conditions is a dynamic process in which understanding evolves, priorities shift, teams gain and lose members, resources become available or disappear, and interventions are tried and found wanting. Creating change is not a linear process but a recursive one, frequently requiring change agents to double back and repeat steps.

Conceptually, the starting point for most change initiatives is the conviction that something is wrong and needs fixing. This is the Problem, the current, unsatisfactory state of things: unhoused people living on the street, a lack of safe places where children can play, a food desert, or too many unsafe apartments owned by slumlords. However, it is also important to remember the issue will appear differently depending on the perspective of those looking at it—in an area with high homelessness, small business owners may perceive the problem differently than those living on the street, or a team of outreach workers, or the staff of a shelter.

Among those looking closely at the Problem will be the Team, the core group shepherding the process by which the old status quo is hopefully changed into a new and better one. This strategic team should be small enough to coordinate and make decisions effectively, yet it must collectively possess, or be able to mobilize, the different capabilities and key assets necessary to achieving the initiative’s goals. As mentioned, this group’s perspective will help define the issue to be worked on, as well as extending or limiting the range of imagined interventions, so a broad, diverse membership is ideal. Members may be selected by a civic leader from different government agencies, nonprofits, corporations, and from within the affected community, and they may join or leave as the project’s needs shift or other circumstances change. (Note that in some cases, a team may exist before a particular problem is targeted, in which case the composition of the team will likely determine the issue to be selected, rather than vice versa.)

Another critical element in this process is the Environment. Visually, the Canvas represents the Environment as enfolding all the other elements, since it is the context within which the Problem exists, the Team is selected and operates, and the change process happens. The Environment may include broad, global trends (such as a pandemic, supply chain issues, and a new respect for essential workers) as well as features of the regional and local contexts (such as state funding for the environment, a city’s process for approving new development, or distrust of the police within a neighborhood). One reason it is important to know the local terrain well is that the Team will likely be assembled from among interested local groups and organizations. In addition, while the Team will probably look at initiatives elsewhere that successfully addressed similar issues, understanding the local Environment and its particular opportunities and limits is crucial to successfully intervening in the problem. It is also important to know the historic causes of the issue and about previous attempts to address it.

The Envisioned Future is the destination: the new status quo that the initiative hopes to bring into being, where conditions are improved and the community is somehow better off than before. To use the homelessness example, the anticipated future could be a city where no one sleeps on the street because permanent housing is prioritized by the government. A clear vision of the intended destination is necessary to guide the change agents and bring others on board—but this vision may also shift over time (for instance, as the problem comes to be understood differently, or as ambitions are scaled back because funding for the initiative is limited).

Central to the idea of public value is that the Envisioned Future is not only achievable but worth the cost—which is where the Public Value Account comes into play. This element of the Canvas helps show whether the change to the status quo has real, articulable benefits to society, ones that outweigh any losses of resources, freedom, and so on. It does this by enumerating the pros and cons of the change initiative: the material benefits and the less tangible ones (such as gains in justice or equity) that accrue to society, and the costs in money, personnel, convenience, and liberty. As wonderful as the Envisioned Future may sound, it can’t justify every possible expense. Just as a business creates a balanced budget for new initiatives to show how expected revenue should pay for outlays, so the Public Value Account is a ledger that lists all likely positives and negatives resulting from the change.

At the center of the Canvas is the Public Value Proposition. This is a single sentence articulating the heart of the change initiative: the problem, the proposed intervention, the target beneficiaries, and what they stand to gain from the change. The Proposition represents not only the ends but also the means of moving from the status quo to the envisioned future—the activities that will deliver the positive benefits of the Public Value Account. Arriving at this sentence obviously requires a great deal of fact-finding about the problem, brainstorming ways to make it better, and back-and-forth within the team about the best way forward. Once all has been distilled into the Public Value Proposition, however, it can serve not only as an “elevator pitch” for the initiative but as a hypothesis for change, to be tested and refined during the rest of the process. One example: “If the city prioritizes funding permanent housing for unhoused people, it could significantly cut the number of people sleeping on the street and in shelters while increasing the effectiveness of other interventions for those individuals.”

Public Value Thinking

Testing the Public Value Proposition means evaluating it with the Strategic Triangle, which consists of Support, Capacity, and Purpose. The Strategic Triangle is an important component of public value thinking, a conceptual tool that can be used to ensure a change initiative is on track and aligned in key ways.

Support refers to the approval of individuals and entities with the positions and/or power to carry out the initiative, usually in the form of funding, permissions, and public spirit. If some of the Support needed to execute the Public Value Proposition is lacking, then either more must be recruited, or else the proposed solution must be scaled back or changed entirely. Capacity refers to the means of actually carrying out the initiative—the expertise and operational resources (such as staff, space, equipment, capabilities, and so on) needed to turn a plan into reality. Again, the necessary Capacity must either be found or the Public Value Proposition must be changed. The Purpose is a little different—stemming from the Envisioned Future and the Public Value Account, it asks if the proposed change is substantive enough to garner the attention and Support of key authorizers. The Purpose must also align with the assembled Capacity, which must be able to actually produce the outcomes articulated in the Public Value Account. Remember, the Strategic Triangle is a tool used to test an idea: by continually checking that all three elements of the triangle are in place, fully considered, and coherent with one another, the team positions itself as well as it can for a successful change effort.

In the homelessness example, Support could include funding from the city and state, special zoning permissions to create new housing, and public sentiment in favor of new housing projects; Capacity could include outreach staff, construction companies, hotels to be converted to apartments, cleaning services, and so on; and Purpose could be the benefits of permanent housing, improved outcomes regarding health and mortality, more foot traffic to businesses, etc.

The Strategic Triangle is useful in other ways, too. When surveying the Environment and considering who should be recruited to the Team, for instance, the three themes of Capacity, Support, and Purpose can be used as lenses for evaluating candidates. Specifically, the leader assembling a team can look for “operators” who possess the expertise and operational command needed to carry out day-to-day operations in service of the initiative (Capacity); for “authorizers” who either have the authority or the influence needed to secure permissions, funding, etc. for the project (Support); and for “arbiters” with lived experience of the targeted issue, or other advocates, who can judge whether the initiative is really working as projected (Purpose).

Another invaluable piece of the public value puzzle is the Five Mindsets, axioms that the entire team must hold in mind, and enact, to make change. The Mindsets are ways of viewing the process of Public Value Thinking that are critical to creating the right culture in which to use the Canvas and other tools. If these principles are not kept in mind, the process doesn’t work.

- Developing, Not Finding: As the team works through the change process, it should expect to find itself constantly diverging and converging around purpose, value, and other ideas. There is not one fixed path or public value proposition buried somewhere and waiting to be found; instead, the team is developing its own doable, valuable, and authorizable path forward through trial and error. The team’s ideas, as well as its environment, are dynamic and always evolving.

- Balance Over Perfection: Relatedly, finding a “perfect” solution is almost impossible. Thoughtful compromise is needed to move ideas forward, and teams should look for balance across their thinking to ensure an idea has a real chance of both being executed and producing the desired public value.

- Thinking Is Acting: It is also critical to remember that the very process of thinking (about the problem, the environment, possible interventions) is in itself a form of action. Even when ideas are abandoned, this is all a kind of progress because thinking changes the conditions in the environment. At a minimum, it changes the potential to take action. By the same token, this means that as the team thinks, and acts, it should keep checking to ensure there is still alignment.

- Context Matters: Positive social conditions are relative. Someone (or a group of people) will need to be the arbiter of whether a change is creating public value—ideally, those most impacted by the change in conditions. Regardless, what is positive for one group may not be positive for others in the local environment.

- Dynamic, Not Fixed: As the team works on a problem, the metaphorical focal length of the lens it looks through will change. Sometimes change agents will zoom out to look at the big picture, while at other times they will zoom in and focus on only one area. To work effectively, the lens should constantly be adjusted. This is true for all components of the Canvas. As the process moves along, the environment, team, ability to gather support, even the understanding of the problem will change. It is critical that the team not mistake a provisional idea or conception for something fixed and static.

Conclusion

To summarize, public value thinking is a cohesive approach to changing social conditions for the better. It can help civic leaders, public servants, and social entrepreneurs get from the status quo to a new and improved future with the assurance that a project’s costs were worth its outcomes. Within public value thinking, the Public Value Canvas is a crucial tool that lets practitioners conceptualize the most important considerations in a change effort (the Problem, Team, Environment, Envisioned Future, Public Value Account, Public Value Proposition, Support, Capacity, and Purpose). The Canvas aids change agents in developing and evaluating their ideas about the selected issue and efforts to ameliorate it, enabling them to check for alignment across the many moving parts of a dynamic situation. When a team leverages the Canvas and other aspects of public value thinking like the Strategic Triangle and the Five Mindsets, they are laying the groundwork for coordinated action that will have tangible benefits in the real world.

A collaboration between George Veth and Mark Moore, the originator of Public Value Theory.